I’ll never forget your smile

Honor for the fallen and compassion for our returning veterans

Dear Ravers,

It’s 1983, and a group of us teenagers are piled into the back of a small pickup truck. It’s night and we’re keyed up after teepeeing a few homes. I’m scared about getting caught and feeling guilty; this will be my first and last acts of “vandalism.”

Sure enough, about two miles from the scene of the crime, red flashing lights appear.

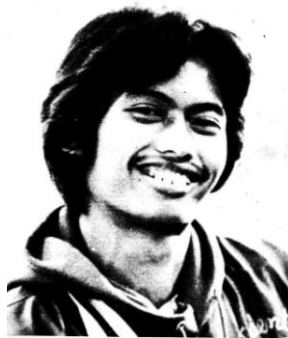

Our classmate, Randy Guzman, is our getaway driver, and I bet he was coerced into doing it. He’s tall and really skinny; probably from running cross country every hour outside of class. He’s always worn really big glasses … almost as big as his toothy smile. If anyone’s going to get us off, it’s this innocent looking kid.

Our classmate, Randy Guzman, is our getaway driver, and I bet he was coerced into doing it. He’s tall and really skinny; probably from running cross country every hour outside of class. He’s always worn really big glasses … almost as big as his toothy smile. If anyone’s going to get us off, it’s this innocent looking kid.

I can’t hear what the cop says to Randy. As they talk, we shove the remaining toilet paper under our legs. After a couple minutes, the cop drives away, telling us to “call it a night.” Later, Randy said the cop wanted to make sure that we weren’t drinking (which we weren’t). The band of straight-laced hooligans is spared from juvey!

The next distinct memory I have of Randy, must be the summer of 1991. A small group of us gathered in our hometown at the parents’ of another friend, Jordan Chroman (bottom picture). Both ROTC, Jordan took the Army route and Randy the Marines, and they’re back from the first Persian Gulf War. Jordan’s parents have thrown a BBQ for the “old gang,” and my future husband, Jim, and I are sitting with Randy on the step on the deck outside. I think this is the first time that Jim has met Randy — and he’s struck by his warmth, by his thoughtful demeanor.

Randy looks the same, with the exception that his once feathered hair is now a buzz cut. He’s not the same goofy kid though. He takes off his big glasses and presses his fists to his eyes. What he experienced over 7,000 miles away, catches in his throat. He commanded a rifle platoon in Kuwait.

Randy looks the same, with the exception that his once feathered hair is now a buzz cut. He’s not the same goofy kid though. He takes off his big glasses and presses his fists to his eyes. What he experienced over 7,000 miles away, catches in his throat. He commanded a rifle platoon in Kuwait.

I don’t see Randy’s face again, until his picture appears on TV and in the newspaper, in his Marine uniform.

See, U.S. Marine Corps Capt. Randy Guzman (two top photos) was among 168 people killed on April 19, 1995. He was working as the XO, overseeing the Marines’ recruiting station in the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. When the bomb went off, he was sitting at his desk. He was just 28. (Sadly, the Marine reservist who found Randy five days later, died on September 11, 2001, while saving the lives of victims at the World Trade Center attack).

A few weeks before the 20th Anniversary of the bombing, I’m on the phone with Jordan, a scheduling accomplishment, as he’s in South Korea, a 15-hour time difference from Reno. He’s now a Colonel and commands the 403rd Brigade headquartered in Daegu. I tell him that I’m working on my annual Memorial Day piece to support the troops, and that day with Randy in his parents’ backyard has been on my mind.

A few weeks before the 20th Anniversary of the bombing, I’m on the phone with Jordan, a scheduling accomplishment, as he’s in South Korea, a 15-hour time difference from Reno. He’s now a Colonel and commands the 403rd Brigade headquartered in Daegu. I tell him that I’m working on my annual Memorial Day piece to support the troops, and that day with Randy in his parents’ backyard has been on my mind.

We talk about returning veterans and the struggles that so many of them face. We talk about the movie American Sniper as an example, and he says that although much of it was “Hollywood,” a lot of it painfully hit home.

He’s very emphatic about the message that he’d like me to share with all of you. “Tell your readers that these soldiers don’t need to be pitied or have excuses made for them. What they need is patience, they need compassion, they need time, they need help.”

He reminds me that less than 1% of the U.S. population serves in the military (compared to 12% in WWII). Meaning that very few of us have any real connection with or comprehension of the life of a soldier. Very few of us can say that our daughter or son, our niece or nephew, our mother or father has boots on the ground.

And with that disconnection, even though through the Internet we have “more access” to what’s happening overseas, most of us are not engaged on a personal level. Nor do most of us understand the real impact of what’s happening politically. Just because soldiers are sent home, it doesn’t mean that the remaining forces that are left, say in Afghanistan, are in a better situation.

So when a vet comes back, they are asked, “Aren’t you happy that you’re home?” “Sure, we’re glad that we’re home,” Jordan tells me, but he also explains that “being home” in civilian life doesn’t always feel “safe or normal.” So that expectation that any veteran can resume “where they left off” doesn’t apply to everyone. Welcoming them back at the airport is just not enough.

We talk about Randy again, and the emotion of that day. In the 30 years since Jordan has been in the military, I’ve never seen him wipe his eyes, and probably never will. That’s what Jordan is trying to get across to me; that every veteran is different in how they process what they’ve seen, some healthier than others.

We’ve been on the phone for nearly an hour, a rare thing. I’m frustrated that I don’t know how I can help when he’s the only soldier in my life now. And I wonder too, if his exhaustion or something else is making him so fervent in this conversation about compassion. When I ask again how I can make a difference, he says that even if one or two of our 5,000 subscribers has a connection with a soldier and understands this message, then I’ve helped.

Here’s to remembering Randy and all of our veterans this Memorial Day.